Opinion

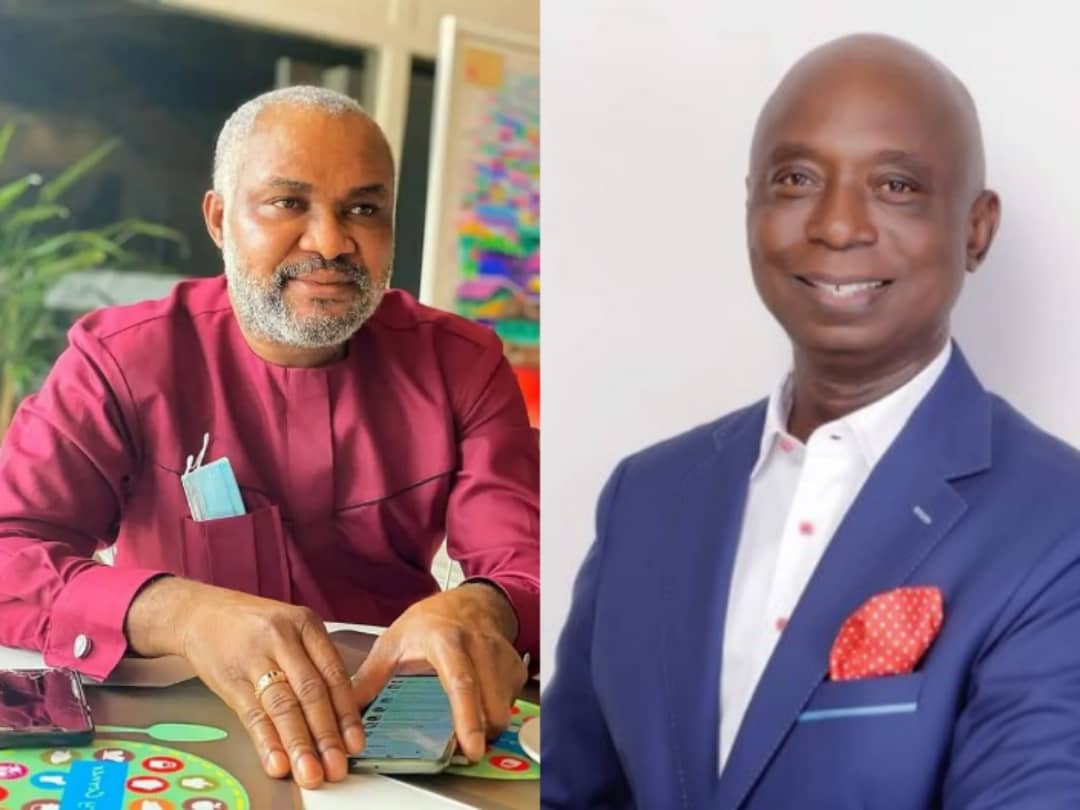

Ned Nwoko’s footprints in the National Assembly, By Emmanuel Onwubiko

“No man can be a competent legislator who does not add to an upright intention and a sound judgment a certain degree of knowledge of the subject on which he is to legislate.

– James Madison”

“Legislators represent people, not trees or acres. Legislators are elected by voters, not farms or cities or economic interests.

– Earl Warren”

“We live in a stage of politics, where legislators seem to regard the passage of laws as much more important than the results of their enforcement.

– William Howard Taft”

Few lawmakers in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic have approached their mandate with the blend of intellectual energy, legislative boldness, and community impact that Senator Ned Munir Nwoko has displayed since his election in 2023. In just two years at the National Assembly, the Delta North senator has emerged as a reform-driven legislator whose record in bills, motions, and projects reflects a deep understanding of what representation should mean in a maturing democracy. His work reveals a lawmaker intent not merely on occupying space in the Senate, but on redefining how legislative action can strengthen the rule of law, inspire institutional reform, and give real meaning to constitutional democracy.

From the day he was inaugurated on June 13, 2023 the numerical markers of his legislative output began to generate notice. He is credited with sponsoring over 27 bills and moving some 20 motions within his first year, thereby placing himself among the most active senators in the chamber. By his own accounting, the total now stands at 31 bills, 25 motions and 51 constituency projects for his senatorial district in two years. These figures matter because in a legislative culture that often emphasises visibility rather than substance, their scale signals a seriousness of purpose: he is not merely participating in the legislative process; he is seeking to shape its agenda.

Yet raw volume is only part of the story. What distinguishes Senator Nwoko is the ambition of his agenda and its alignment with several key pillars of constitutional democracy: the rule of law, equitable representation, social justice, and institutional reform. One of his most telling legislative interventions is the bill for the creation of Anioma State (SB 481). This bill is more than a regional tweak; it speaks to the question of fairness in federal representation by proposing that the South-East region should have six states, like other regions do, and thereby aim to equalise the number and voting strength of their representatives in the National Assembly. It is difficult to overstate how radical such a proposition is in Nigeria’s federal calculus: it challenges entrenched norms, provokes difficult conversations about identity and equity, and places a Senator at the heart of national reform rather than mere regional development.

On security and defence, he proposed an amendment to the Act establishing the Nigerian Defence Academy, to locate a new NDA campus in Kwale, Delta State (SB 332); a move that aligns military capacity with underserved geographical zones and suggests an intent to redress structural imbalances. Further, he tabled a bill to alter the Central Bank of Nigeria Act (SB 672) to prohibit payment of salaries and remunerations in foreign currencies in Nigeria; a bold shot at structural anomalies in the economy and a push for fortification of national sovereignty.

These are not pedestrian legislative initiatives. They reflect a mindset attuned to constitutional architecture, fiscal integrity and national security. They advance the respect for the rule of law in the sense that they seek to impose clarity and accountability in areas where regulatory gaps have long existed. Senator Nwoko’s motions also show this orientation. He moved a motion demanding redress for the 1967 Asaba massacre, and a motion on the need for reparations for historical injustices and mitigation of neocolonialism. In doing so, he is tapping into the raw energy of national memory, and bringing to the parliamentary floor issues that speak both to justice and to democracy’s deeper dimensions of inclusion and reckoning.

In the project-space, the Delta North Senatorial District under his watch has seen more than mere handing-over ceremonies. Reports show completed solar-powered street lights in Kwale, Idumuje-Ugboko and other communities; boreholes and solar-powered water schemes; medical outreach to hundreds of constituents; security equipment to personnel; as well as infrastructural interventions such as the rehabilitation of stretches of the Benin-Asaba expressway. These physical manifestations of policy and representation matter because they tie parliamentary activism to tangible improvements in citizens’ lives. There is no guarantee that every bill will pass, or every motion will produce change, but the district projects embed the law-maker in the daily realities of those he represents.

From a democratic standpoint, this dual approach (legislative activism plus constituency development) can be said to deepen the trust-contract between the governed and the governing. Democracy is not simply about elections and rhetoric; it is about rights being enshrined in law, institutions being strengthened, and resources being fairly shared. Senator Nwoko’s interventions suggest that he is reading this broader map of governance, not isolating himself in the micro-politics of patronage but aligning his legislative footprint with a national vision.

His work advances constitutional democracy in at least three concrete ways. First, by challenging existing constitutional arrangements (as with Anioma State), he reminds us that the constitution is not a static relic but a living document that must respond to evolving realities of representation. Second, by engaging with laws on security, economics, public service, diaspora voting and social support, he advances a broader understanding of citizenship, rights and state-responsibility. Third, by bringing these issues into the Senate floor, he strengthens the public-institutional bridge: legislatures matter, they initiate ideas, frame national discourse and hold the executive to account.

In respect of the rule of law, his record emphasises legislation rather than arbitrary executive fiat. By framing policy in statutory change, by tabling bills that require debate, amendment and passage, he is re-affirming the principle that law governs and not whim. The proposal to restrict daytime movement of heavy-duty vehicles (SB 698) is an example of how everyday regulatory gaps (road-safety) can be swept into the legislative ambit. Moreover, his motion on the surge of kidnappings in the FCT, among other security issues, shows that he understands governance is not only about grand bills but about urgent national threats. Respecting rule of law means anticipating that law serves citizens, not merely power; that the vulnerable are protected and that the state’s obligations are not deferred indefinitely.

Beyond these, Senator Nwoko is carving a reputation as a statesman and in a country where the term is easily invoked but rarely substantiated, this is critical. What defines a statesman is not only the breadth of interventions but the willingness to transcend narrow interests, to engage in inclusive rhetoric, to anchor one’s actions in principle rather than expediency. By championing issues like diaspora voting, social security reform and the establishment of institutions such as the National Talent Rehabilitation and Integration Agency, he signals that his compass is national in scope, not parochial. His moves encompass not only Delta North but Nigeria’s systemic architecture and future generations.

He also demonstrates responsiveness; a key trait of statesmanship. The training, empowerment, and grants to youth and women in his district reflect the idea that representation is not a one-off election but continuous service. Over 500 constituents were each empowered with cash grants of N100,000 after skills training, as part of his three-phase empowerment programme. Such initiatives reinforce the idea that democracy is not only about rights in law, but capability in practice: the right to train, the right to thrive, the right to be supported.

Still, while celebration is due, the journey is incomplete. Legislative ambition must translate into sustainable institutional change. Bills sit in committees, reforms take time, and the optimist must temper expectation with realism. A high number of sponsored bills is a noteworthy metric but not the final measure of impact. Their passage, implementation, oversight and evaluation matter. Constituency projects must avoid being mere flashpoints for photo-op and instead embed durable systems of empowerment and infrastructure maintenance. Statesmanship also demands consistent integrity, transparency and courage in the face of resistance, especially when one’s interventions challenge elite interests.

In assessing whether Ned Nwoko’s footprints will endure, one must ask: will the bills become laws? Will the motions lead to accountability? Will the projects be maintained and leveraged for broader development? In principle, yes, they can; but that requires political will, institutional cooperation and citizen vigilance. His legislative record sets the stage; implementation must follow. His engagement with questions of identity, social justice and systemic reform sets an important tone; follow-through must anchor the results.

What remains undeniable, though, is that by his own admission and as corroborated by multiple reports, Senator Nwoko has moved the needle. He has elevated the idea of what a Nigerian senator can do; from mere representation to active institution-building, from patronage to policy. He has placed himself in a lane where the national question of democracy, rule of law and equitable growth are not peripheral but central. That is the mark of a man not simply occupying an office, but seeking to expand its meaning.

For Nigeria’s democracy to deepen, it needs more individuals who see the legislative chamber not as a place of ceremony but as a workshop of reform, and more senators who link law-making with service on the ground. Ned Nwoko’s footprints in the National Assembly are tangible evidence that such linkage is possible. Whether his example becomes a standard for others remains to be seen, but the fact that the benchmark has shifted is itself a positive. He invites his colleagues (and the citizenry) to judge accomplishment not by visibility alone, but by substance, by durability, by the capacity of a Bill to protect, a law to serve, and a project to transform.

In a country where representation is often measured by what one brings home rather than what one reforms, the dual agenda he pursues makes his footprints meaningful: in form, in content and in consequence. Ultimately, the strongest legacy a legislator can leave is not simply the bills he sponsored but the institutions he strengthened, the rights he extended and the people he empowered. On that measure, Senator Ned Nwoko’s work to date suggests he is building that legacy; and in doing so, leaving footprints that future lawmakers will have to run to catch up.

* EMMANUEL NNADOZIE ONWUBIKO is the founder of the HUMAN RIGHTS WRITERS ASSOCIATION OF NIGERIA and was NATIONAL COMMISSIONER OF THE NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION OF NIGERIA.