Opinion

Tasks before Nwoko’s reparations’ committee, By Emmanuel Onwubiko

“There’s no doubt that when it comes to our treatment of Native Americans as well as other persons of color in this country, we’ve got some very sad and difficult things to account for. I personally would want to see our tragic history, or the tragic elements of our history, acknowledged. I consistently believe that when it comes to whether it’s Native Americans or African-American issues or reparations, the most important thing for the U.S. government to do is not just offer words, but offer deeds.

– Barack Obama

What I’m talking about is more than recompense for past injustices—more than a handout, a payoff, hush money, or a reluctant bribe. What I’m talking about is a national reckoning that would lead to spiritual renewal. Reparations would mean the end of scarfing hot dogs on the Fourth of July while denying the facts of our heritage. Reparations would mean the end of yelling “patriotism” while waving a Confederate flag. Reparations would mean a revolution of the American consciousness, a reconciling of our self-image as the great democratizer with the facts of our history.

-Ta-Nehisi Coates”

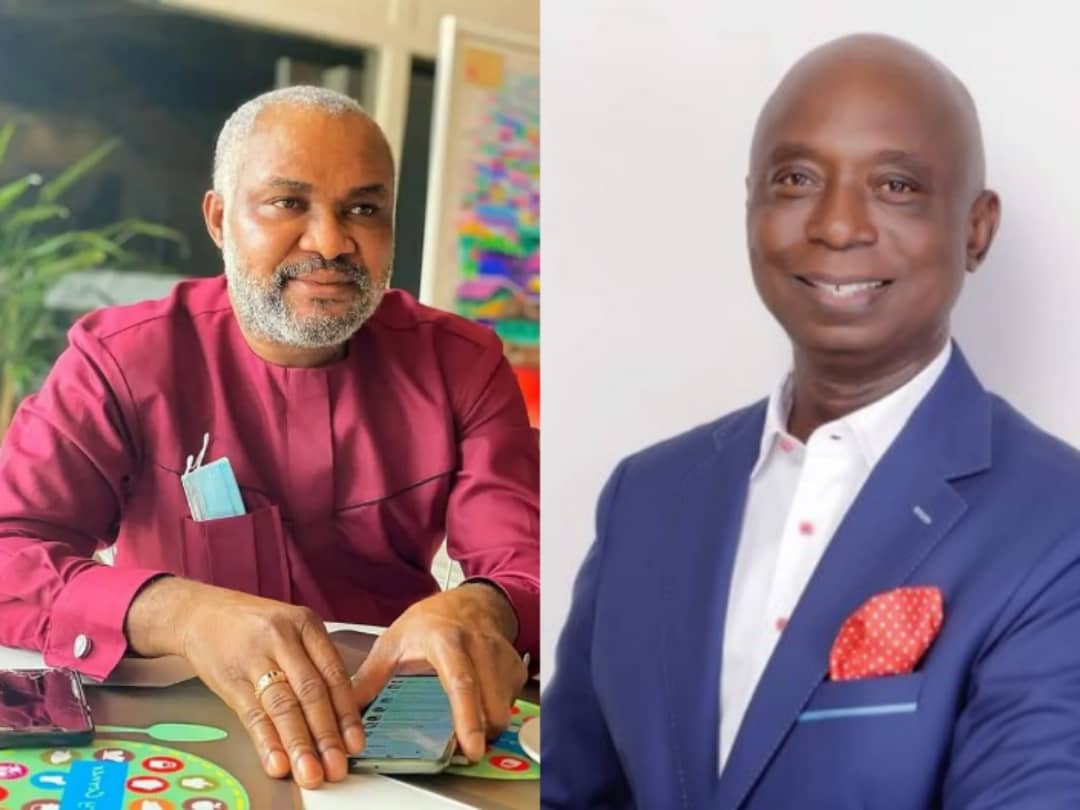

For the first time in Nigeria’s legislative history, a committee of the National Assembly has stepped into a domain long reserved for global moral debates; the pursuit of reparations for slavery, colonial exploitation, and the economic vandalism that shaped the modern world. Under the leadership of Senator Ned Munir Nwoko, the Senate Committee on Reparation and Repatriation has not only altered the vocabulary of Nigeria’s diplomacy but also redefined the nation’s role in the international justice conversation.

What unfolded at the United Nations Headquarters in New York on October 14, 2025, was not another ceremonial engagement dressed in diplomatic pleasantries. It was the visible emergence of a serious policy direction; one that confronts the lingering moral and material consequences of colonialism through legislative and multilateral mechanisms. Facilitated by Nigeria’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and coordinated by the office of Senator Nwoko, the Global Summit on Reparations and Repatriation represented a deliberate attempt to move Africa’s historical grievances from the periphery of emotion to the centre of law, economics, and global conscience.

The hybrid side event, held in Conference Room 6 of the UN Headquarters, brought together policymakers, scholars, historians, human rights advocates, and representatives of the African diaspora and the Caribbean. It was not a gathering of the wounded seeking pity; it was a coalition of the aware, demanding justice. The conversations, the symbolism, and the intellectual depth of the summit reflected a new confidence in Africa’s ability to define its own moral agenda in the global system.

Senator Nwoko’s strategic push for reparations has thus become one of the most intellectually consequential legislative initiatives to emerge from Nigeria’s 10th Assembly. It transcends the optics of advocacy; it signals a new paradigm where the legislature takes an active role in global justice diplomacy. The presence of international experts, youth representatives, and Caribbean voices at the UN event validated this ambition, turning what might have been dismissed as a political experiment into a credible movement backed by research, historical evidence, and moral urgency.

READ ALSO:Why Ndigbo must unite for Anioma State now, By Emmanuel Onwubiko

For far too long, Africa’s place in global discourse has been defined by the vocabulary of aid, pity, and dependency. But the tone of this event (anchored by Hon. Gloria Okolugbo, representing Senator Ned Nwoko, and presided over by Senator Aminu Abbas), was radically different. It was the sound of a continent reclaiming its agency. Every presentation, every intervention at the summit, reaffirmed the painful but unbroken continuity between Africa’s colonial past and its present underdevelopment. As Dr. Sontoye Briggs poignantly observed, the scars of colonialism are not buried in the past; they bleed daily in the form of economic inequity, forced migration, and the systemic exclusion of Africans from global wealth structures.

The summit was a tapestry of emotions, intellect, and conviction. Mr. Ephraim Emilimor, representing Africa’s youth, brought the house to stillness with his poem, “The Man Across the Street Called Africa.” His words distilled the essence of centuries of exploitation; capturing Africa as a neighbor humanity has long ignored, yet whose spirit remains resilient. The performance transcended art; it was a moral metaphor for what reparations must mean, not just money, but the restoration of identity, humanity, and dignity.

Perhaps one of the most compelling interventions came from the President of the Bonair Human Rights Association, an associate member of the CARICOM Reparations Commission and an organization in Special Consultative Status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council. She called for the creation of a joint African-Caribbean Council for Reparative Justice; a platform through which nations historically wronged could act in concert. The significance of that proposal cannot be overstated. It signals a move from scattered voices to a united global coalition capable of engaging former colonial powers from a position of collective moral strength. The era of fragmented demands is over; the age of coordinated justice has begun.

In his welcome address, Senator Ned Munir Nwoko articulated a principle that should anchor the global reparations discourse: apologies must precede restitution. He called upon nations that participated in the transatlantic slave trade and colonial exploitation to offer formal apologies as a moral prerequisite to structured reparations. His words resonated deeply across the hall: “Acknowledgment of wrongdoing,” he said, “must serve as the foundation upon which restitution is built.” This framing is not only politically strategic but ethically sound. It establishes that reparations are not acts of generosity; they are obligations of justice.

The adoption of The New York Declaration on Reparation and Repatriation at the summit was another historic milestone. The document, painstakingly crafted and negotiated, embodies the consensus of heads of states, parliamentarians, legal experts, and representatives of the United Nations, the African Union, and CARICOM. It affirms that reparations and repatriation are not mere symbolic gestures, but essential instruments for global justice, reconciliation, and a renewed African renaissance. The Declaration calls for unreserved apologies from colonial powers, the repatriation of Africa’s stolen artifacts, and the creation of dedicated international institutions headquartered in Africa to coordinate and monitor reparations initiatives.

This Declaration marks a paradigm shift. For centuries, the world has acknowledged the crimes of slavery and colonialism in rhetoric but refused to translate that acknowledgment into restitution. By anchoring this discussion at the United Nations, Nigeria’s Senate has succeeded in internationalizing Africa’s claim within the moral and legal frameworks of global diplomacy. The New York Declaration situates reparations as a shared global responsibility, not an African grievance.

The participation of diverse actors in this summit (from youth representatives to seasoned diplomats), reflects the inclusive approach Senator Nwoko has championed since he first moved the motion for the establishment of the Senate Committee on Reparation and Repatriation. The Committee has already demonstrated an impressive spate of work. Within a short time, it has mobilized the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, engaged ambassadors from African nations, and initiated dialogue with regional bodies such as the African Union and ECOWAS. These actions signal a seriousness of purpose rarely seen in Nigerian parliamentary initiatives. For once, a committee of the National Assembly is not only deliberating but leading at the international stage.

Senator Aminu Abbas, Vice Chairman of the Committee, captured this spirit in his closing remarks when he described the summit as “the beginning of an irreversible journey towards justice and restoration.” He referenced successful precedents such as Japan’s reparations to wartime victims and South Africa’s post-apartheid truth and reconciliation framework, underscoring that reparations are not utopian ideals but achievable realities when anchored in political will. His remarks were both affirming and forward-looking, acknowledging Senator Nwoko’s vision as a catalyst for global dialogue on reparative justice.

The participation of Hon. Gloria Okolugbo, who anchored the proceedings, added another dimension to the summit. Her call for the United States and other Western nations to reform their visa policies toward Africans, especially those engaging in legitimate business, research, and cultural exchange, brought the conversation home. Reparations, she argued, must also translate into dismantling the structural barriers that continue to marginalize Africans in the present global order. She reminded the audience that economic inclusion and human mobility are contemporary expressions of justice. Her remarks underscored that reparations must be holistic; encompassing both the restitution of stolen wealth and the dismantling of institutionalized prejudice.

From the perspective of national significance, the Senate Committee on Reparation and Repatriation embodies a profound shift in Nigeria’s engagement with its colonial past. Previous generations of African leaders have often approached the issue of reparations as moral advocacy. What distinguishes this Committee is its institutional approach; its determination to transform moral claims into actionable policy. It recognizes that for reparations to move from the realm of rhetoric to reality, there must be legal frameworks, diplomatic strategies, and sustained international lobbying. In this sense, the Committee represents a convergence of historical justice and modern statecraft.

Nigerians and Africans alike have every reason to look to this Committee with cautious optimism. The Committee’s mandate (if pursued with the diligence it has already shown) could yield transformative outcomes. Beyond financial restitution, reparations could take the form of technology transfers, educational exchanges, debt forgiveness, and targeted development initiatives that address the structural inequalities bequeathed by colonial exploitation. Repatriation, on the other hand, could restore to Africa its cultural heritage; its stolen artifacts, sacred relics, and the intangible pride of identity long held hostage in foreign museums.

But beyond expectations, the Committee must also guard against the pitfalls that have historically derailed such noble causes. Bureaucratic inertia, political distractions, and the temptation of tokenism are threats that must be confronted. For this Committee to succeed, it must operate with transparency, accountability, and scholarly rigor. It must document, quantify, and present irrefutable evidence of Africa’s historical losses, translating moral outrage into legal argumentation. It must build alliances not only within Africa but across the diaspora, academia, and civil society. Reparations, after all, are not demanded; they are negotiated.

The role of Nigeria’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in facilitating this UN event is equally commendable. It signals a growing recognition that foreign policy must reflect national conscience. By aligning with the Senate’s initiative, the Ministry has shown that diplomacy can be a tool for justice, not merely for state interest. The global resonance of the summit underscores that the moral weight of Africa’s history cannot be silenced indefinitely. The world is beginning to listen; not out of charity, but because justice demands it.

For Nigeria, this leadership moment comes at a time when the nation itself is in search of moral rejuvenation. The reparations agenda, if sustained, could redefine the country’s global image from a state often associated with internal corruption to one that stands at the vanguard of moral diplomacy. It could also inspire a new generation of Nigerians to view politics as a tool for transformation rather than opportunism. Senator Ned Nwoko’s initiative is a reminder that leadership, when anchored in conviction and intellect, can transcend borders.

The Committee’s next steps are therefore crucial. The proposed reconvening in March 2026, where a communiqué modeled in the United Nations format will be adopted as a global working document, presents an opportunity to solidify the momentum. That communiqué must not only outline principles but define actionable frameworks; establishing timelines, assigning responsibilities, and proposing mechanisms for enforcement. To ensure continuity, the Nigerian government should institutionalize the Committee’s work through legislation that embeds reparations advocacy within the nation’s foreign policy architecture.

Internationally, the Committee should explore partnerships with academic institutions and legal experts to quantify the economic costs of colonialism; much like Caribbean nations have done through the CARICOM Ten-Point Plan for Reparatory Justice. The establishment of an African Reparations and Repatriation Institute, as proposed in the New York Declaration, could serve as a continental hub for research, policy formulation, and international litigation. Such an institution would ensure that Africa’s pursuit of justice is not episodic but sustained.

On the moral plane, the summit in New York rekindled a powerful truth: justice delayed is not justice denied if pursued with conviction. The emotional resonance of the event (the poetry, the testimonies, the collective resolve) was a reminder that reparations are not just about the past; they are about the future of human civilization. They challenge the world to confront its hypocrisy—to move beyond celebrating freedom while profiting from its denial.

As Senator Nwoko’s Committee advances this mandate, it must continue to speak not in the language of anger but of justice; not as victims, but as custodians of humanity’s conscience. The global movement for reparations will only succeed if it is framed not as retribution but as reconciliation; a collective healing process through which the world acknowledges its shared guilt and shared hope.

History will remember that in October 2025, in a modest conference room at the United Nations, Africa (through Nigeria’s Senate) raised its voice with clarity and dignity. It will remember that Senator Ned Munir Nwoko, driven by a vision larger than politics, summoned the world to a moral reckoning. It will remember that in the heart of New York, the descendants of the enslaved stood tall and declared that their story would no longer be told by others.

For Nigeria, this is more than a diplomatic milestone; it is a moral rebirth. For Africa, it is the beginning of justice long deferred. And for humanity, it is an invitation to finally make peace with its own conscience.

*EMMANUEL NNADOZIE ONWUBIKO IS THE FOUNDER OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS WRITERS ASSOCIATION OF NIGERIA AND WAS NATIONAL COMMISSIONER OF THE NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION OF NIGERIA.